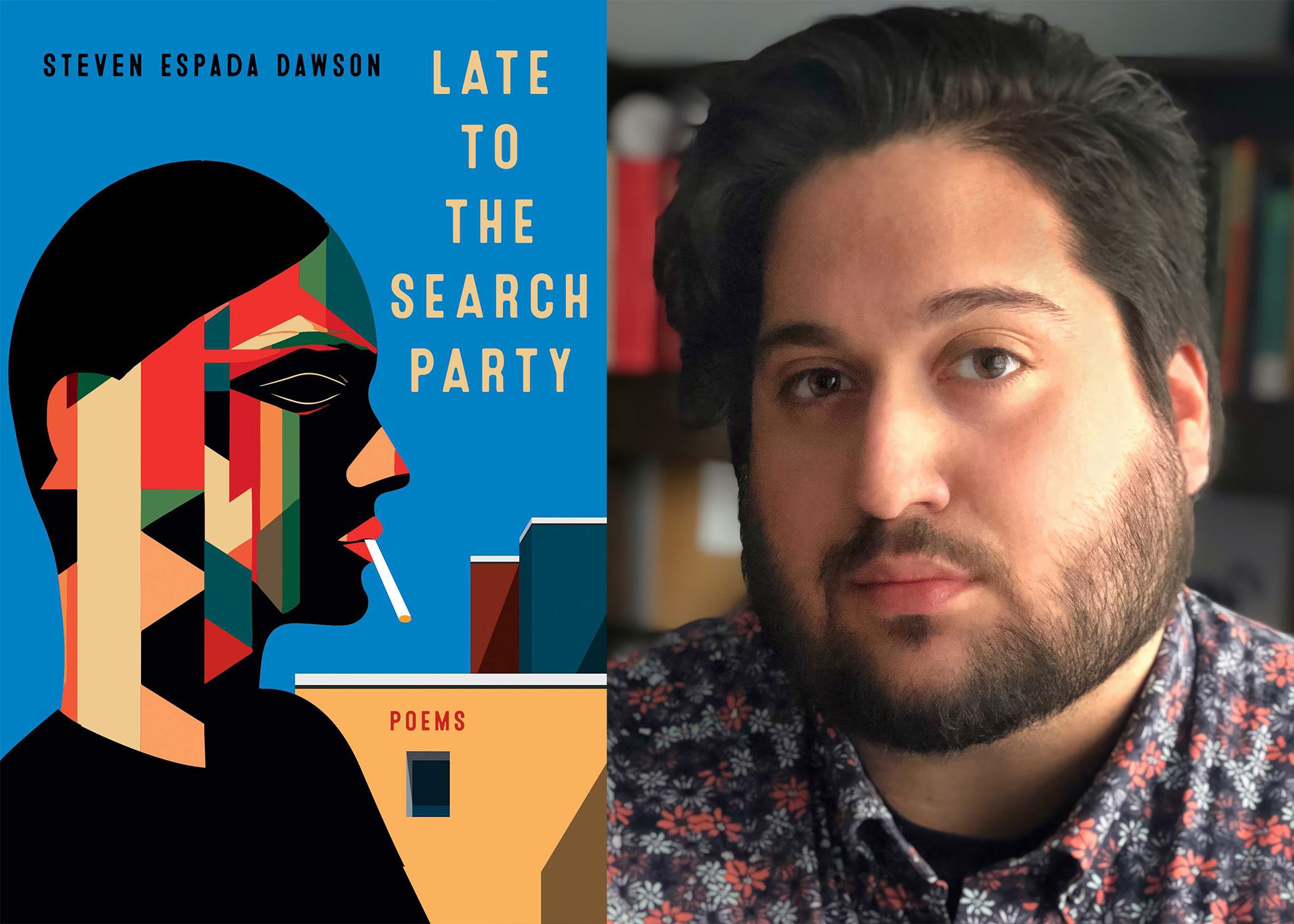

Kurtiss Limbrick: First off, I'd like to start by saying congrats on your debut collection of poetry! When you were writing the poems that make up Late to the Search Party, did you write each of these poems with the intention of compiling them together as a book, or was it more of an organic process?

Steven Espada Dawson: Until very recently, I never wrote poems with a book in mind. The "project" before the book has very much always been helping me help myself by writing toward understanding. How do I really feel about something? How is my family living? What is the shape of this life? What can it be? I got an MFA, in part, because it gave me three years of health insurance and the writing time to lean into that project of knowing. It was an investment in myself and my mental health. I really didn't feel like I was writing a book until my grad thesis was a pile of printed papers scattered across a long desk.

There are two exceptions to this. The last two poems I added to the book were written/finished during my time working with my press editor, Kathy Belden. These poems, including the title poem, felt kind of like filling in the holes that nails leave in a wall. That final touch before you leave an apartment you're renting. Those two pieces added a slightly stronger feeling of cohesion and sense of place—something usually more palpable to the writer than the reader, so I had to adjust with that in mind.

KL: I love how you've put that - the final touch before you leave an apartment. And truly, those last three poems feel like the final touches. In the title poem Late to the Search Party, the poem ends with you finding your brother's body, specifically with your relief. And the last lines of Ars Poetica With Passing Hailstorm ends with you saying "Watch me busy myself with finishing line" and finally, you end the collection with the poem Elegy for the four Chambers of My Mother's Heart which starts with the lines: "This is an elegy, and believe me, it will end / within the small walls of your townhome." It feels as though the collection comes full circle in this way.

With your approach to these poems in mind, writing toward understanding and leaning into that project of knowing as you've put it, I'd like to hear about your writing process. How did these poems come to you, and how do you approach them on the page? Is there a particular ritual you followed, or a setting you placed yourself in to get the juices flowing?

SED: As someone living with OCD, my entire life revolves around resisting rituals that affirm my obsessions and compulsions. I am lucky that writing exists outside of that orbit. It is something that is constantly moving away from me—either by an absence of inspiration and freetime or an excess of exhaustion. In truth, even when I have free moments, I find writing very difficult most of the time.

I've become better at managing what I can control by giving myself to the moments where nostalgia or beauty or strangeness lock eyes with me. When this happens, even at the most inconvenient times, I've learned to lean in. I'll hide myself in a restaurant's bathroom, get off the bus early and sprint to a bench, turn off the burner where I'm sauteing onions and garlic, whatever. That's how I've learned to write, to meet the page where it's at. This is a somewhat chaotic process, and I've learned to bow to it.

KL: I'm sort of relieved that you've mentioned how writing is constantly moving away from you. I have felt that way personally recently, and I'm sure many readers will be able to relate to that as well. The creative process isn't always as simple as sit, write, publish - and it sounds as though your writing process has been evolving along with you and your life, your career, your hobbies.

In an interview with Surging Tide you mention that writers should take risks with their work and write towards their discomfort. I'm curious, with this creative evolution in mind, how do you continue to take risks in your writing when the poem comes to you? And what were the biggest risks you took while writing the poems that make up your upcoming book?

SED: I did a reading shortly after Late to the Search Party was picked up. During the Q&A portion of the event someone in the audience asked me what I believed (and still believe) to be a too-personal question for a reading: "If you knew your brother was alive, would you want to see him?" I responded with a joke, "You'll have to buy me a drink first..." and quickly moved on to the next question. On the inside I was deeply uncomfortable, even actively agitated.

For better or worse, I realized that the manuscript—despite already being picked up—never really answers that question. And to be clear, I don't think it "owes" that information to the reader. But, as I mentioned, I write to figure out how I'm feeling, and I learned I hadn't really fully reckoned with that question on the page. This inspired me to revisit scraps of a poem I wrote two years ago. That poem, which contains something like "an answer" is now the title poem of the book.

I think people, and especially new writers, should prioritize safety before anything. Writing toward discomfort can be an access point for discovery, especially if you are someone trying to actively untangle your experienced trauma. That's not the only venue for discovery, though—BIPOC, Queer, and Disabled poets are constantly proving that writing toward joy, pleasure, care, etc. can be just as powerful.

KL: With that sense of prioritizing safety, I wonder what you can share with us about the vulnerability of being a poet. This collection brings readers (and in the case of your readings, listeners) along through that highly personal experience of family, addiction, illness, trauma, and finding your way through it all. How has that expression of vulnerability helped you, or hindered you as an artist, a teacher and a person?

SED: I grew up in a household where talking about mental health was an overwhelming and unwanted intimacy. "Depression" and "anxiety" were just suburban words I learned at school—words that ran against the desire to align with machismo values. But my upbringing was marbled with trauma and a lot of feelings I didn't know where to put, and I expressed those feelings in unhealthy ways. Until I met poetry, I didn't have a vessel to overflow into. My friend and former professor, Kaveh Akbar, wrote to me once: "Remember, the poems can hold what you can't, if you let them." I'm not sure if it's true for everyone, but it's true for me.

It's a dagger, though, to be vulnerable. Talking about highly personal aspects of your life—even in spaces like this—can feel like someone's looking at you from the other side of a one-way mirror. Sometimes there's no room, no mirror, just a stranger asking you too-personal questions after a reading or an angry email from an anonymous hater. But I'm also lucky to get messages through my website from folks who've resonated with my work. They say a particular poem has helped them cope or helped them give themselves permission to write toward discomfort. For now I've decided that the public vulnerability is worth the risk.

KL: I hear what you're saying about vulnerability being a dagger, and yet, it's wonderful to know that through poetry, there can be so much connection. That resonation, that community, and this affirmation you mention, from showing others the ropes with your own courage, and being able to share the victory of overcoming the heavy hands of life together. It really is something to be grateful for.

You've mentioned before that writing for you is not necessarily about being published. We've touched a little on what function writing serves for you, but I'm also curious if you can share your "Why" for writing?

And as a follow up to that, in an interview with the Cap Times you said for both the Wisconsin Institute of Creative Writing fellowship and the Madison Poet Laureate position, you didn't think you'd be selected, but applied anyway. As an artist, how do these awards impact/affirm your work and what would you tell those who are seeking that sort of validation, or are too afraid to apply?

SED: I think my "why" for writing has always been a moving target. When I was a boy, I wrote scripts for my action figures. My world was small, and I was motivated by the many silences of our home. When I was a teenager, I wrote my first ever poem to win a contest for an iPod Nano I gifted to a beloved. I was motivated by young love and the tornado of puberty. When I was in college, I wrote poems I thought a younger version of myself might find helpful for his survival of another timeline. Then, I wrote poems to learn about how I was genuinely feeling in this beautiful, ulcerated world. Poetry helps me be a better witness to it and widens my capacity for being permeable to it. It's an exercise in empathy. But just like an "exercise," writing is just practice for the real thing, not the action itself. A poem is not your spit stuck to a riot shield or the measly dish of macaroni you bake for a friend whose hometown is being bombed.

I think you should write significantly more poems (whatever "poems" means to you) than you seek to publish. It's so important to have work that is not tied to an end product or attached to anyone's assembly line (though I need to acknowledge the demands laid at our feet are divvied out disproportionately). The best advice I have for folks actively applying for opportunities is to let other people tell you no. Sometimes we can be our own gatekeepers. There are also real gates, real barriers, and it's okay to ask for help! Many places will let you submit for free, including fellowship applications, if you reach out. I've had to several times myself.

KL: It's such a wonderful thing to see how a writer's "Why" for writing can develop, and I always love hearing about different artists' motivation for creating. Thank you for sharing that evolution!

Your upcoming collection is full of poems that I feel are an active effort to empathize both with your family, your brother and yourself, and it's a collection that reckons with the reader because of that intimacy, and strength of feeling. Poetry is so important because it is an exercise in empathy, both in reading and writing and I really admire how you encourage readers, writers, etc, to keep that in mind. To practice it in the world to any extent available. I think that's really valuable.

I want to thank you so much for your time and attention and this conversation! I'm so excited for your work and your words to be introduced to the world. I really think that the level of vulnerability, empathy, and humanity that you weave into your work as a writer, as poet laureate, an educator and as a person is so crucial to our world right now. So thank you.

My last question for you is whether there are poets or writers that you recommend every student of poetry read, and similarly, what poets or artists were crucial to your development?

SED: Thank you, Kurt, for taking the time to read the collection. I am grateful for your thoughtful questions.

At the end of every semester I have thirty-minute one-on-ones with all my students where I go through my library and recommend ten or fifteen books to them—with little blurbs of what I think they might take away from each one. These recommendations are student-specific, based on the work they turned in during our time together. It's one of my very favorite things to do. I'm hesitant to point folks to a mount rushmore of poetry, but I always encourage writers to read widely and outside of their comfortable palates. Toward that effort, I think literary journals are irreplaceable. (In addition to Hunger Mountain, of course!) Split Lip, Muzzle, and Waxwing are three of my favorites doing it right now. Their curation is undeniable, and their issues are all available for free online. I'm thinking about that Gregory Orr poem that goes "How lucky we are / That you can't sell / A poem, that is has / No value. Might / As well / Give it away. // That poem you love, / That saved your life, / Wasn't it given to you?"

When My Brother Was an Aztec by Natalie Diaz and Black Aperture by Matt Rasmussen feel like the godparents of Late to the Search Party. I owe these poets and their poems some portion of my life. I think if you enjoy them, you'd probably like my book.