Annelise Schoups: What was your first introduction to Lucille Clifton's work, and do you remember what specifically captured your attention about it?

Kazim Ali: My sophomore year of college I took a class called Black Women Poets, but I’d loved Black poetry since I was in high school. We never really read writers of color in my classes, with very few exceptions. As far as poetry goes, we were mostly studying people like Wordsworth and Shelley. If we studied any contemporary poets, it was really widely read poets, people appearing in the New Yorker, for example, like Sharon Olds. I do remember we read a Gwendolyn Brooks poem.

Somehow, on my own, I found in the school library an anthology edited by Dudley Randall called The Black Poets, which had a lot of the Chicago-based poets that were associated with the Black Arts Movement, including as he's known now Haki R. Madhubuti—he was called Don L. Lee at the time—Mari Evans, Sonia Sanchez. Nikki Giovanni was in that anthology, Etheridge Knight was in that anthology. And I read another anthology by Arnold Adoff, called City in All Directions, which was an anthology of urban poets, which included many writers of color.

And the way language was being used by these communities was so exciting to me. It was not the language of Wordsworth or Sharon Olds for that matter. As somebody who grew up in a multilingual household, where lots of people spoke different kinds of languages that I understood but I couldn't speak, I felt divorced from a more formal literary English. I felt very excited—enamored even—thinking about the way that Black writers were using English.

So, this course I took on Black Women Poets, the professor of that course, Barbara McCaskill, who teaches at University of Georgia now, introduced us to Lucille Clifton, and many other writers: Angela Jackson, Colleen McElroy, Leslie Reese, and other Black women poets. I was learning Lucille Clifton in the context of all the other Black women writers.

We read Next and we read Good Woman. Those were the two books that were assigned to us, and "cutting greens" was one of the first poems by Lucille Clifton that I read. It was very exciting. The rhymes, the sound, the intensity, but also the wisdom of it—the real devotion and generosity of the poetry—just captivated me. And always has since that moment! I've been reading her ever since.

AS: What was the impetus to start teaching her work?

KA: Well, I didn't teach poetry for a long time. The first five, almost seven, years of my teaching career, I was teaching composition and other kinds of literature. My first academic appointment was in the Department of English, at Shippensburg University and I was teaching a little bit of poetry, but also fiction, composition, and Middle Eastern Literature. I taught some American Literature survey courses, too, but I was not teaching contemporary literature or poetry, where I would have been able to teach Lucille Clinton.

By the time I got to Oberlin College, I was in the Creative Writing program and the Comparative Literature Program, so I was teaching translation and translation studies and poetry workshops, but I wasn't teaching a lot of craft classes or literature classes anymore. Even when I came to UCSD, I was bringing her poems into classes, but I wasn't teaching whole books of hers. For this upcoming academic year, I proposed a whole course on Lucille Clinton that I will be teaching next spring.

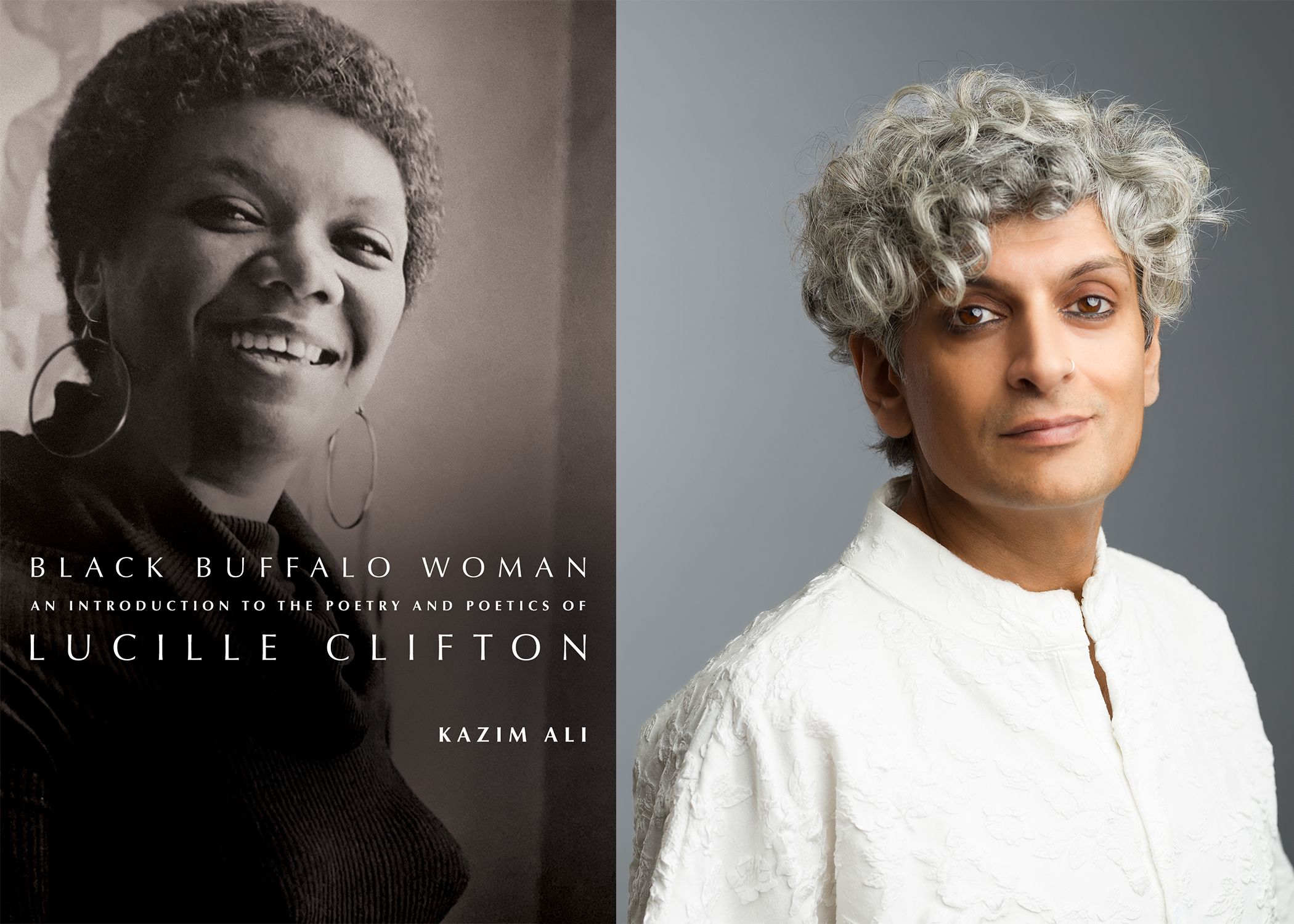

But it's also hard to teach what you love. Because you might not have thought about it in a critical way specifically. You might love something but not want to delve into it or dig into it in the context of literary study. One of the things I noticed about Lucille Clifton is plenty of people love it, and plenty of people were writing about it, deeply and academically in interesting ways, but I didn't see a book for a general readership that reveals some of the layers and complexities and social and political contexts present in the work. So, I really wanted to dig deeper, but for general non-academic audiences.

AS: My understanding is that most of the essays in the book were born from lectures; What is it that you hope your students take away from her work?

KA: It did grow from lectures I gave through an on-line series called The Writers’ Annex, run by the Community of Writers, an organization that runs summer workshops in Olympic Valley outside Tahoe. Clifton taught there for a long time, so I offered two four-week courses through the Writers’ Annex; the book grew out of the first four-week course; by the time the second course came around, the book was out and we used it as a text for the class.

The subtitle of the book is “An Introduction” because I didn’t want it to be exhaustive. I really love the idea that someone would read the book and then read a Lucille Clifton poem I talked about and see a new dimension to it. Or read a Lucille Clifton poem I didn't talk about and think, "I could write about that poem!" And there’s plenty I didn't talk about.

The book is 300 pages long but there are so many poems. Her collected poems is something like 750 pages, and then there's Generations, the prose memoir. And there's plenty of unpublished poems that are in the archives that were not included in books. So, there's a lot to write and think about. Mine can't be the last word.

AS: In the book, you talk about how she's labeled as simple, but there is very obviously a lot of intention and thought that goes into her rhyme scheme and syllabic stresses, etc. Do you think there was some subconscious awareness of sound without being aware of it?

KA: Well, it’s her language that has been called simple. She contested the notion that simple language meant simple thought. She very much wanted to be accessible. But, as she pointed out, accessibility doesn't mean easy or simple. It can still be deep and layered and complex and intellectually rigorous but be accessible to read. And that's what she is: she's accessible. She's neither simple nor easy, especially for someone who read as deeply as she did from a young age.

From 12 or 13 years old, she was interested in poetry. And her mother, Thelma Sayles, was a very different kind of poet, but she would read her British poets, like Shelley and Leigh Hunt and Thomas Wyatt. And then Clifton herself talked about reading A.R. Ammons and Conrad Aiken, these formal, formal poets. And William Blake! She knew all of them. And I think she was developing an ear. I don't think any poet sits around doing all that in their first writing, but eventually you develop an ear.

Then, when you're writing, you have a sense of the line and a sense of rhyme and a sense of assonance and sonic activity within the poem. And she really did revise! I saw her archives! I saw earlier versions of the poems and later versions of the poems, and you could see how she was revising as she went along. So, there was a lot of intentionality, even if it was instinctive.

AS: She has that line in one of her poems where she says she doesn't know how she does what she does in the way that she does it. Do you think that she downplayed the intention with which she wrote or maybe it just came naturally to her?

KA: She says that, yeah. It's true in a sense, she had a finely tuned ear from years of listening to her mother’s recitation, but also, she particularly mentions the pastor at the church in her community—the rhythm and pulse of his orations—you can really hear church cadence in her work, I think it’s true. In another sense, it's a little bit of a pose, because she really didn't downplay [her skill]; in interviews she talks a lot about her technique.

She says, “I don't know how I do what I do” in that poem because that's a poem about her being the only Black poet in rooms full of white poets. And that happened to her a lot. And she wasn’t a poet who wrote a lot of critical prose (or any critical prose), besides a few reviews here and there, and the very occasional poetics statement.

If you look at the interview in “Poets & Writers” Magazine that came out in April 2000, she was very conscious of the fact that there were other Black poets and poets of color who were excluded where she was being let in. And, so, she would mention those poets, including Sonia Sanchez and Li-Young Lee.

In that particular interview, she talks about Sonia Sanchez extensively because she felt like she herself was being let into spaces, like the Board of Chancellors of the Academy of American Poets, and being invited to Dodge Festival and other places, whereas someone like Sonia Sanchez was not being invited into those spaces.

And I think Clifton was aware of why as well. Sonia Sanchez was overtly political, radical, and Clifton was plenty political, including in her work, but maybe in a more palatable way. That’s changed by now, but it’s important to remember how different things were, even twenty years ago.

AS: Let's talk about accessible language and her being cast as a simple writer, which she resisted. I'm, quite frankly, obsessed with the quote where she says, “I'm interested in being understood, not admired.” Why does the concept of simplicity seem to hold such a negative connotation, and is it specifically frowned upon within the world of poetics?

KA: Well—and I talk about this in the book—she felt the opinion of her work being described as simple or easy was racialized. And that's why she made that point about accessibility and difficulty. She didn’t really have time for an opaque poem. She didn't like it. She didn't like reading it. She didn't feel like she wanted to write that way.

When Clifton wrote, she had a sense of wanting to write for people who are not just literary people or educated people or people who know about poetry. She wanted to write for all people. She wanted to write, in particular, as she has said, for women, for Black people, and for everybody. It was part of her aesthetic and poetics to be accessible.

But, I think, you give something up as an artist to do it, to be accessible. You sacrifice something. I'm sure she didn't feel that way. I’m sure I’m saying something that she didn't feel for herself, but there are regions of poetry you can't explore if you're just saying, “I want to write something that the neighbor can read,” then you’re foreclosing lots of possibilities in poetry.

But she had this strong sense of voice and, like I said, none of it meant ease. None of it meant simplicity. It's incredibly complex work. If you can write a 300-page-long book explaining poems, it means you're not just reading it and understanding it. In one whole chapter, Chapter Eight, I talk about the poem, “sarah's promise” for—I think—almost 20 pages. I talk about one poem of ten lines, and I could have kept going. So that's not simple work.

And I talk about her prosody more generally with other poems, but I wanted to do a really deep dive on that one poem, and then I wanted to leave it. Give the reader some tools and then let people discover it on their own. Someone could write a 300-page book just on her prosody. And maybe someday someone will do that. It won't be me, but someone should!

AS: I'd like to talk a little bit about the concept of naming because it shows up a lot in the book, and I got the impression that she sort of toggles back and forth between the importance of it. Examples include the way Caroline refuses to share her name, and, in contrast, the poem in which Clifton shouts her own name, writing, “i call my name into the roar of surf / and something awful answers.” Then, in All Us Come Cross the Water, there's Tweezer, who's unconcerned with the origin of his own name, but who then sets the main character straight by saying, “Boy named Ujamaa oughta know.” Do you feel naming was significant to her, or that it was subjective or circumstantial, or that she wanted us to question its importance?

KA: I think it was completely important. The question of why Caroline would not reveal her name is perhaps answered by Tweezer’s when he tells Ujamaa, “Somebody don't got your name, they don't really got you.”

I talk a little bit about Dionne Brand's book Map to the Door of No Return, where, at the beginning, the niece is trying to get the uncle to remember what African nation they were from. And Ujamaa has the same concern in All Us Come Cross the Water. He keeps asking his family, "Are we Ashanti? Are we Yoruba?" He wants to know, and no one can tell him. What Tweezer and Ujamaa's parents, and Caroline by denying her name, are trying to say is that it's the present that's important. The past has been taken. We don't have it anymore.

Of course, Roots by Alex Haley and Lucille Clifton’s Generations came out in the same year. And then there was the work of Toni Morrison, who was Lucille Clifton's editor at Random House. So, you have these three, different Black writers. Throw Alice Walker in there and throw Gloria Naylor in there. Toni Cade Bambara. There is this generation of Black writers who were struggling with the question of how to write a history that has been obliterated. It doesn't exist anymore, and they all have different answers for it.

Alex Haley did archival research and then embroidered as fiction (he called the novel “faction”). Alice Walker used actual mediumship. She signs The Color Purple “A.W. author and medium,” acknowledging the contributions of her ancestors as well, writing, “I thank everybody in this book for coming.” NourBese Philip did something similar with her book Zong!, attributing it to an ancestor, saying “as told to the author by Setaey Adamu Boateng.” While Lucille Clifton, who takes the social and makes it extremely personal to the family, recounts in Generations the stories of her ancestors as she heard them through family lore. Of course, she was closer to history. Alex Haley had to go back many generations; he didn't know the people personally, whereas Clifton’s father was raised, until the age of eight, by his own great-grandmother Caroline, who had been enslaved. So, Lucille Clifton is one degree removed from an enslaved person. She's one degree away from an enslaved person. She's close to it.

You see that in her poem “quotations from Aunt Margaret Brown,” where Aunt Margaret Brown is writing about the Lunar Landing and Martin Luther King and all those things. Margaret Brown, Caroline Donald's sister, died at some point between the end of the 19th century in the early 20th century; she did not live until 1968.

With Clifton, sometimes she is channeling, sometimes she is writing in personae. Besides automatic writing and divination with Ouija board, Clifton also experimented with past-life regression and hypnotism. All of this she describes in her work. She actually wrote a manuscript about it called Curiosities that's in her archives. She eventually decided not to publish it.

This is speculation—my impression from conversations with her about it—but I think she decided not to publish it because she wanted to be taken seriously as a writer. She would jokingly say, “America's not ready for that!” I think she knew it would be weird for people to see her doing this past-life regression and writing in the voice of an enslaved person. She did eventually publish some of the poems she felt were channeled—a sequence from the 1970s—in her 2004 book Mercy.

I fully understand Clifton’s hesitations, though at the very same time, James Merrill was doing Ouija Board experiments and literally winning the Pulitzer Prize and winning the National Book Award for those books. I do not at all discount Lucille Clifton’s concerns. I think she was right to be apprehensive about how people might respond to her doing the same thing.

Marina Magloire, who is one of the scholars currently writing about this so-called "Spirit Writing" points out that Lucille Clifton's work in this area exists in a tradition of mediumship of Black women, Black women prophets, including Alice Walker, of course.

AS: There's a lot of spirituality in her work. Actually, I was a little surprised by the number of biblical references. And you said something about how she sort of assumes her readers have a familiarity; she doesn't prompt anybody about them. The same is true for the poems in the beginning, the Buffalo War poems about Tyrone and his little brother. How important do you think having a foundational knowledge of these dogmas, or even some of these other flash points in popular culture, are to understanding her poems?

KA: It’s true that she doesn’t explain. With the biblical poems and the mythological ones, there’s a lot of information in the poems themselves that help you understand, but I do think the understanding is richer if you know the original texts. There's no notes in the books. There's no context at all. That's part of why I wanted to write all of this background in Black Buffalo Woman, to really let people understand the levels of complexity and intertextuality.

Regarding the Buffalo War poems, you really do get a sense of Tyrone and Willie B. reading those poems, no matter what you know about the long, hot summer or Muhammad Ali or Jackie Robinson; you can still kind of understand it. But my hope is that by giving the additional background, it will enrich the work even more.

And the bible wasn’t her only text. She was also very interested in the contemporary moment, including pop culture. She has poems about Lorena Bobbitt, Clark Kent and Superman, Aunt Jemima, Jesse Helms, and so on.

AS: And you said she famously refused to explain. She always kind of asked more of her reader or her listener, right? She wasn't afraid to say, “You can do some work here.”

KA: Right. I remember at readings, she had a very small voice, even on the microphone. People would always say, “Can you speak up?” and she would say, “Listen harder!” And there was something political in that, as a Black woman writer. Refusing to be at the beck and call of the audience. Asking them to move.

Even the biblical stuff, with the context of Blackness, like the "jonah" poem for example, is about slavery. He says, “and if i had a drum / i would send to the brothers / —Be care full of the ocean—” It's a reference to the kidnappings, the selling into slavery, in the clothes of the familiar story of "Jonah and the Whale."

And, in the poem “slaveships,” the slave ships become the whale “who vomit us out from ships.” That verb vomit is the verb from King James, of Jonah being vomited up by the whale. The slave ships are vomiting the slaves up on the shore.

So, to know all that context makes the poems richer. But if you don't know that context when you read the poem “slaveships,” it's still so intense. It doesn't matter if you know that the verb vomit is the same as the verb from King James. The closing gesture of that poem is also a call back to a much earlier poem by Robert Hayden about slave ships.

AS: That's arguably the hallmark of a strong poem: that there's more to it every time you read it. Knowing how much time you’ve spent with her work, if you were to recommend one poem or one collection or book of hers to beginners, what would it be and why?

KA: One poem is hard because there's so many! But one book? Well, I'm going to say Mercy, which came out in 2004. In Mercy, she writes about the death of her two children. Her daughter Rica died in 2002, from cancer, at age 39. And her son, Channing, died in his sleep in 2004 of an undiagnosed heart condition. So, she writes quite intensely and painfully about those deaths, but the book also has poems in different types of interesting formal structures, and, significantly, as I mentioned before, the only published poems from her voluminous spirit writing. There's probably six or seven hundred pages of her automatic writing in the archives and a sequence of about 25 pages from that corpus is published in Mercy. It's called “message from the ones.”

If you're going to read only one Lucille Clifton book, or you want a book to start with, I would say Mercy is going to give you the best of every part of her. Then, of course, you're going to want to read everything.

AS: Very early in the book, you express a concern that you might be projecting your own interest in formal poetry onto a poet who only wrote free verse. I have the sense that we all project our experience onto poets and their poems in some way. Does it matter whether we as readers make stuff up?

KA: It does matter! But a poet who publishes wants to be read.

People will read in different ways and interpret in different ways. What I wanted to be able to do was to show the richness and the depth and the skill of her work; I wanted to say that this is a writer to take very seriously. If there's a thesis to the book, it's that. At the very end, I say she's as good as Whitman, Dickinson, Auden, Elliott, Stevens, Brooks, Ginsberg. She's on that level. She should absolutely be considered on that level, and read deeply and seriously.

There's so much to learn from her. And all I wanted with this book was to bring more people to her work, to get people to really, really think about her. Think about the way that she saw America, and when she wrote about America. We’d all be richer for it.

And, if you remember from the book, I had the fortune of knowing her phone number and I called her that very day and she disabused me of any notion I was projecting, saying she was glad I was writing about her relationship to prosody and form.

AS: How has reading and knowing Clifton influenced your own work?

KA: This is a question people really want to know because they read my work and they say, “I don't see the connection here.” But it's really about sound and rhythm and the intensity of spirit, even though we're very different poets and we write very different poetry. I became a poet by reading her work.

People ask Susan Howe this question about her relationship to Emily Dickinson, but if you read Susan Howe's poetry out loud, Dickinson's all over it! The influence of Dickinson is all over it. The philosophical bent of Dickinson is all over it. I think Lucille Clifton and my relationship is, if I dare to say it, comparable to that relationship.

It's about rhythm. It's about sound. It's about intent and spirit. There's a real affinity for me there. I don't know that I could ever explain it.

AS: Is there anything else you want to share about the book, Clifton, or her work?

KA: There's a range of young scholars who are doing incredible, amazing work on Clifton right now. She died in 2010, and these scholars all have been coming up since then. There’s Kevin E Quashie at Brown University, Sumita Chakraborty at University of Virginia, Marina Magloire, who I mentioned, is at Emory. Omar F. Miranda is at University of San Francisco. Bettina Judd at Emory. William Fogarty at the University of Central Florida. So many others.

My book is really meant as an introduction. It's the only monograph on Clifton since her passing. It might be time for someone else to write a book on Clifton, like The Bible and Lucille Clifton or Lucille Clifton's Prosody or Clifton and Keats or anything that gets in there deeply. I talk about her children's work in Chapter Seven, and there should be a whole book on her children's writing! I would be very excited if my book opened doors for people to continue exploring. Nothing would make me happier than to see 10 more books about Lucille Clifton.