Montserrat Andrée Carty: Your beautiful book is on such a personal and difficult subject matter, and in the prologue, you note “Three years ago I put this book away. Too depressing, the marketing folks at the publishing houses said.” I wondered how you took care of yourself during the process of revisiting these painful memories, and when did you feel the time was “right” to put the story on paper, so to speak?

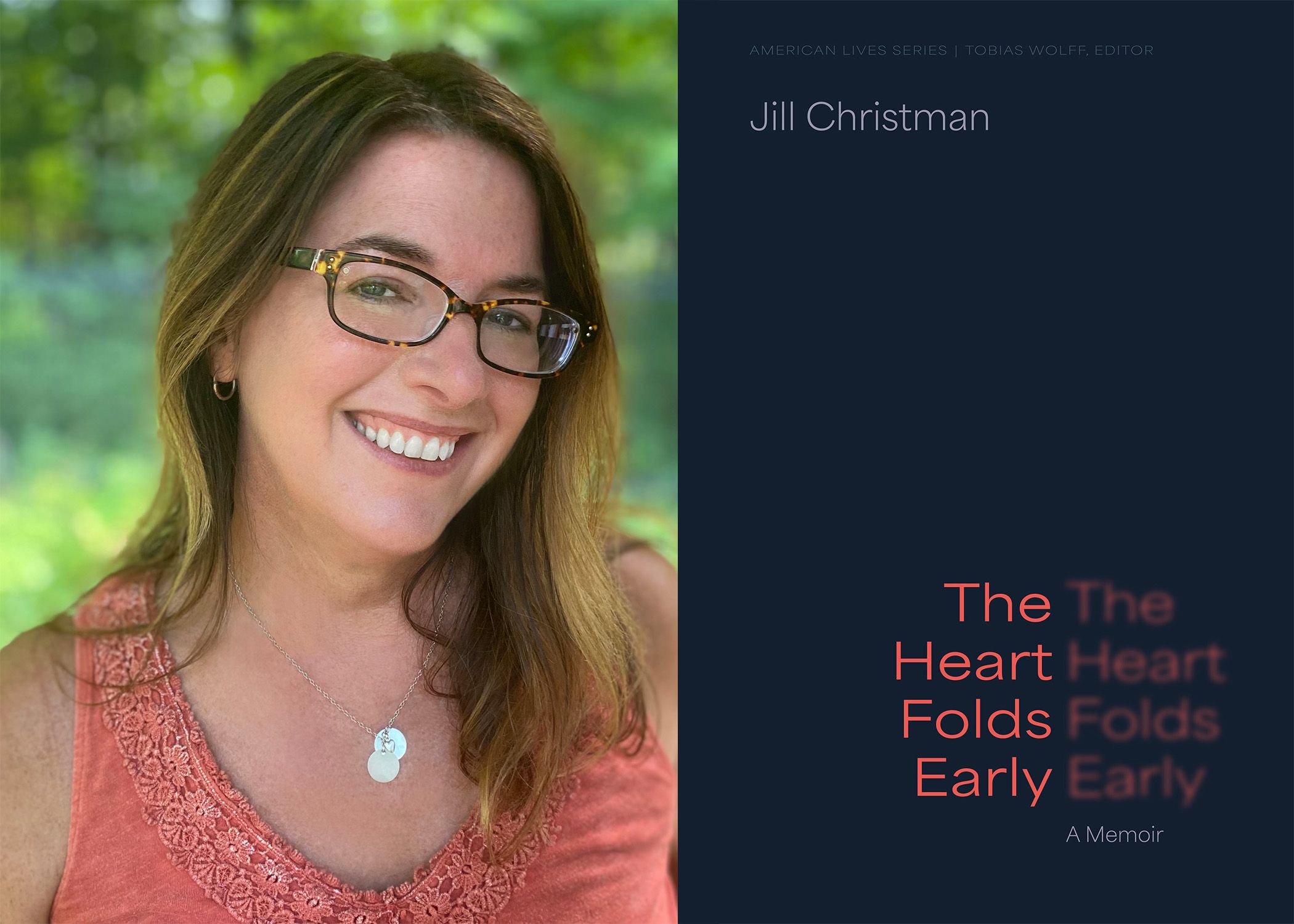

Jill Christman: I began writing the story of losing our baby in fragments and images on the day we got the terrible news of his diagnosis and throughout our time in Chicago—I remember specifically making a note about the rainbow we saw out the window of the Congress Hotel, arching over Grant Park, as the laminaria rods began the work of opening up my cervix too soon to let him go. The beauty almost killed me. I wrote intensively in the years right after the abortion as I tried to hang onto another pregnancy, so that’s why the details of those years are so fresh and vivid in the book. I wrote them down.

But when I first tried to publish a version of this book—through an agent, to big presses—the feedback we got from editors who didn’t want to touch the book stuck in my mind. The book was too depressing, not the kind of memoir the marketing team could pitch as a baby-shower book, and even that “motherhood has been played out” (huh?)—and I let this feedback wear me down. I wondered if it was beyond my skills and capacity to figure out how to tell the story of my choice to have a mid-term abortion to save my baby from suffering. I had other things to write, other stories to tell, and so for some years, I gave up the fight. Some stories we can save for ourselves. Others can wait.

And this one waited until the summer of 2022 when the Supreme Court overturned Roe. I think I knew in the moment I heard the news of the Dobbs decision that I was going to open the manuscript and rewrite the whole thing from that moment. I was so mad and I felt such responsibility to tell my story. After that, during the two years it took me to rewrite the book, I’d say that it was the writing itself that took care of me. Writing is how I protect myself. Writing is how I give shape to the loss. When I revisit something hard in the act of writing, I am in control of that moment in a way I couldn’t be as those events were unfolding, so I’ve come to understand that rather than feel scary, the act of writing feels safe to me. In writing, I am inside my own power. Writing is how I keep myself whole.

MAC: In certain sections, you speak directly to people in the book (“Children of mine, if you’re reading this, flip forward a few pages.” Or, to an ex––“So, hello, Frank.”). I loved this, and don’t see memoirist doing it a lot! Could you please share a little about what it’s like for you, as nonfiction writer, to write about people close to you (or people from your past) and the choices around it? It’s something we all struggle with in CNF and I’d love to get your thoughts!

JC: Thank you for noticing this! I’m trying to write a craft essay about how and why we break down the fourth wall in memoir—and your generous question leads me to something important. In The Heart Folds Early, I’m not breaking down the wall willy-nilly, like the Kool Aid Man crashing through the bricks to a general audience, I’m pulling down the wall brick-by-brick, person-by-person. Sometimes, as you note, I’m thinking about how having to read about their parents’ love story could really ick-out my kids—and truthfully, my children are the most important readers I can imagine moving into the future, long after I’m gone, so they are always on my mind. I’d forgotten about that note to the ex-boyfriend I call Frank, and that makes me realize how fully I let the whole cast of characters into the room while I was writing and revising The Heart Folds Early. Frankly—pun intended—this strategy flies in the face of the advice I give to writers of nonfiction who are feeling nervous: “Write only for yourself,” I say. “Send everyone else out of the room.” And I believe this advice, and certainly, for me, when I wrote my first memoir in my late twenties—Darkroom: A Family Exposure—I was writing only for myself. But this time was different. This time I needed to invite everyone in, and once they were there, it would have been rude to not talk to them directly! In addition to my own beloveds, I also directly address people I have never met, most crucially, the mothers of babies who shared our son’s diagnosis and chose to carry—or try to carry—their babies to term. I want those mothers to know that the choice I made was specific to me and my baby. I want those mothers to know I don’t judge all of the different choices we make every day out of love for our children. I think these mothers are the reason I needed to break down the fourth wall: We are all in the story of this country on this planet in this time together.

MAC: There is a beautiful story you share about your English teacher unexpectedly offering you a generosity, when you desperately needed it. Of this you write “This kindness alters the course of my life.” I think so often about these seemingly small kindnesses that are transformative, and how much they are needed, especially with all the cruelty in the world. Less a question, more an invitation to say anything you’d like on this!

JC: Thank you for this invitation! And yes—what you say. Kindness is transformative. A single, small gesture of kindness can shift the trajectory of a life. I try to remember that when I’m worn down and thinking about not really listening to someone who needs me to listen, or you know, being a jerk in whatever situation might inspire me to be a jerk. Speaking of choices. Obviously, Miss Chase’s kindness was a huge one, right? I mean, here I was, one of hundreds of students she taught every year, and she offered me a room in her home as if it were nothing, as if she sheltered girls who’d gotten themselves into a bad situation every day. For years, I made that into a kind of joke—sure, bookish folks such as myself say that their high school English teachers saved them. But mine? Mine literally saved me. And yet, it wasn’t until I was thinking hard about Miss Chase’s invitation to give me a place to stay that wasn’t my way-too-old-for-me boyfriend’s bed that I understood the full value of what she had offered me: Miss Chase changed the conditions of my life so that I had the safety to make a real choice. When I was seventeen, Miss Chase showed me what real consent could look like—and, wow, did I ever like what I saw. Without her, I may not have made it out of that town and off to college. I likely would not be writing these words now. It's impossible to know when and how I’m paying that kindness forward, but I try.

MAC: You write, “In my Writing classes, I advocate for a strategy I call ‘opposite world.’ When things have gotten dark, sentence after sentence, opposite world helps you find a way to turn on a light, a real light, even the tiniest of sparkles––a lantern, a star, a lightning bug.” And then, you go on to write your own “opposite world” during a time of unimaginable pain. Can you speak a bit more to how this great strategy helps both the reader and the writer?

JC: Opposite world! In writing our toughest moments, it’s always helpful to turn on a light—or in reverse, perhaps everything feels wonderful in our miniscule corner of the world we’re writing: Maybe then, it’s time to look toward our neighbor and make sure she’s doing okay, too. Opposite world. The basic idea is to rotate perspective, to deepen the scope of our vision by changing the angle. It’s never all bad—and it’s never all good either. The passage you’re bringing us to in The Heart Folds Early is right at the point where I’m arriving in Chicago, having traveled out of our home state of Indiana, for the procedure that will end my pregnancy. I am reeling from the news that at nineteen weeks gestation our baby has been diagnosed with a heart defect that is “incompatible with life” and steeling myself physically and emotionally for the surgery. The world feels impossibly dark. I am crushed by grief. All these things are true and I have a friend—a dear, sweet, loyal, brilliant, ray-of-sunshine-in-the-darkest-room friend who is coming to care for our three-year-old daughter while we go to the hospital. In writing this terrible, terrible day, I need to give my reader some of the light Sherrie gave us in those dark days. I mean, she arrived at our hotel with a Poppins-esque bag full of treats: a cloth doll with tiny green high-heeled shoes! Opposite world.

MAC: Speaking of opposite world, I love the way you insert humor and lightness into your book, even in those especially gut-punching sections. Is there anything you might want to add about the importance of making way for humor during the darkest times in our lives?

JC: It’s hard to know how to talk about the humor in The Heart Folds Early. In my many years as a writer of nonfiction—and human moving through the world—I have taken on a lot of tough subjects (such as sexual assault, disordered eating, accidental death, and addiction) and I have learned to laugh when I can laugh—without self-censure. When I take myself too seriously? Now that’s funny. As writers and readers, not only do we need the relief of a moment of levity, but laughter helps us move more deeply into the hard stuff we’re navigating. Without laughter, we might give up—or want to leave. Humor helps us stay. This memoir about making a devastating choice is not a devastating read. One early reader told me she found herself laughing—at least once—in every chapter. And that made me happy. She gets me. The humor often emerges through the characters of my husband or children—funny folks, all—or simply when a situation is just so absurd we can’t help but laugh. I mean, what is with these ob-gyn fellows who pat our knees and call us “Mommy”? That’s just silliness.