W. Dennis Percevecz: You created a film and a book. Which came first? Did one project push the other and how?

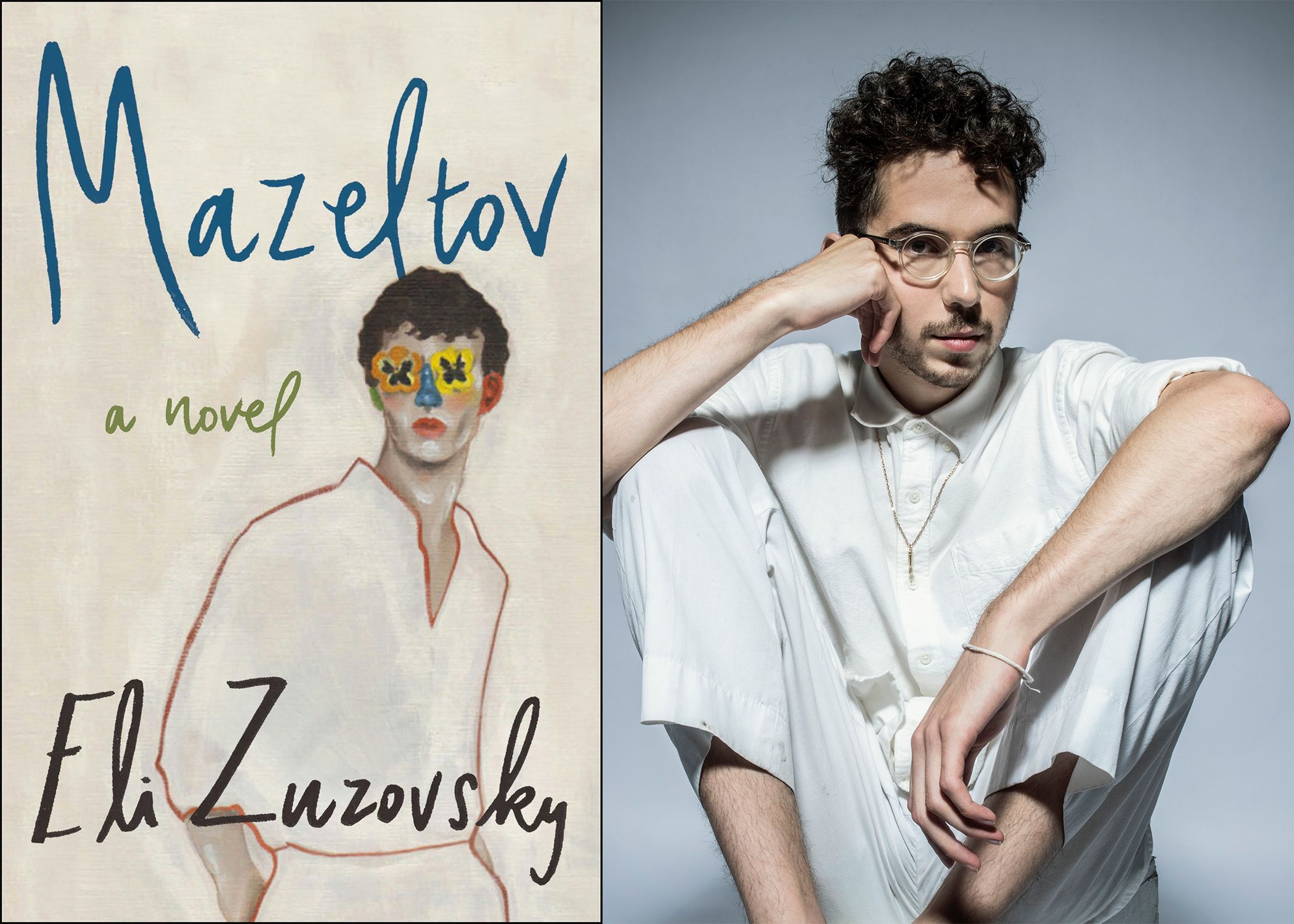

Eli Zuzovshy: The whole project started as my senior thesis in college, where I studied filmmaking and English literature. Since I was a double major, I had to make something that would put the two fields in conversation with each other. I decided to make a film and a book that would share the same setting, characters, and plot. My hope was to use this as an opportunity to meditate on the relationship between film and literature, two distinct—yet complementary—modes of storytelling, capable of pushing the boundaries of each other’s imaginative powers. Working on the film allowed my characters—the amazing actors I was fortunate enough to work with—to talk back to me, which was profoundly useful. Then, writing the novel’s first draft as we entered post-production was an opportunity to both expand and deepen my fictional world.

WDP: Is there a book that you would recommend to LGBTQ+ writers as a must read (other than Mazeltov)? And, with your own books, is there a message that you were hoping to convey?

EZ: I often struggle with the idea of a must read; I think of writing and reading as intensely subjective experiences. One queer book I admire is Audre Lorde’s Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982). I think that queerness—both in life and fiction—presents a lovely opportunity for reimagining and innovation, and Zami beautifully does both. It’s completely singular. With it, Lorde invents a new form, which she calls “biomythography”—a blend of history, biography, and myth.

My job, the way I see it, is to tell compelling stories. When I sit down to write—a film, a play, a book, what have you—I don’t think about conveying messages. What fuels my writing often is posing questions. One question that was often on my mind when I was writing Mazeltov was how we live together—especially in a place as fractured and violent as Israel—and how we make and unmake one another. Sometimes, I thought of the novel as a symphony, where the different instruments and movements echo and converse with one another. I was interested in the idea of the self, which is, to me, a fluid, porous thing, whose development is always intertwined with other people.

WDP: Were there any LGBTQ+ authors in particular that inspired you or influenced your perspective in telling your stories?

EZ: Too many. Lorde is definitely one of them, as is James Baldwin, one of my all-time heroes. I wrote my master’s thesis on the French author Marcel Proust, and he’s a writer that I find myself regularly turning to. Queer filmmakers have also played a huge part in my life, from Chantal Akerman to Cheryl Dunye to Apichatpong Weerasethakul. I find their work—their courage, creativity, and insight—deeply inspiring and meaningful.

WDP: What was your writing process like for Mazeltov? And, do you have a set writing routine?

EZ: I’ve wanted to be a writer ever since I can remember, and as a kid I had very romantic ideas about what writers do and how they do it. This is something that I’ve been trying to undo in my adult life. I think my writing has been at its best when I’ve managed to deromanticize the process and think of it, to the best of my ability, as just another job—or as Zadie Smith puts it, as “something to do.” So the answer, I’m afraid, is pretty boring, which is exactly what I’ve wanted it to be. I try to write every day, for as much time as I can afford myself, with as few distractions as possible.

WDP: How have readers responded to Mazeltov?

EZ: So far, the book has come out in North America and the United Kingdom, and the response in both places has been fantastic. The novel is mostly set in 2009, on the night of Israel’s first invasion of Gaza after its 2005 “disengagement” from the enclave. The book came out in February, while Gazans were still being starved, massacred, interned, displaced, and tortured at the behest of our atrocious Israeli government. I’ve loved hearing from readers around the world about the different ways in which the book has resonated with or impacted their thinking on the present. Seeing them grapple with the questions that the book raises—questions I’m still grappling with in my own life—has been a great pleasure.

WDP: On page 167, there seems to be an abrupt shift to Khalil’s point of view. This is something that many writers struggle with, or are told not to do. How is that you pulled this off rather smoothly?

EZ: As you can probably tell from the novel, I’m fascinated by questions of voice and perspective. In the novel’s penultimate chapter that you mention, “Boys,” I was specifically interested in thinking about the uniting potential of queerness, which can help us come together across differences without erasing them. I was also thinking about questions of complicity and solidarity, as well as the inseparability of political consciousness from any meaningful process of maturation. To tackle these questions, I felt like both perspectives—Adam’s and Khalil’s—were needed, even if such movement between points of view wasn’t the literary norm.

WDP: Was there an event that inspired you to write Mazeltov?

EZ: There wasn’t a single event that inspired me to write the book, but it did grow out of my love-hate relationship with the coming-of-age genre, which is extremely prevalent in our culture. Coming-of-age stories, including some of my favorite ones, often strike me as too narrow. They don’t quite resonate with my own experience, which involved a lot of other people and their growing pains. I think this narrowness—the intense focus on the linear development of one individual almost to the point of fetishization—has a lot to do with the systems under which many of us live, like capitalism and the nation state. I wanted to write something more expansive and capacious that would reflect my experience of growing up as a lifelong and communal journey, where interconnectedness played a crucial role. The novel’s polyphonic structure—the use of different points of view, voices, and styles—is very much part of the book’s backbone and ethos.

WDP: What was the most difficult part of the writing process of this book? How did you meet that challenge?

EZ: I mostly wrote the novel during my senior year of college which unfortunately coincided with Covid, a time of extreme disruption and uncertainty. Most of the challenges I faced were material and emotional; they had less to do with the writing itself and more with the outside world. Like many people, I was deeply concerned about the health, safety, and livelihood of my loved ones as well as my own. Writing Mazeltov and immersing myself in a creative process that excited me and gave me hope was almost like a refuge.

WDP: What is your advice to budding writers? Is that advice different if the writers are writing in the LGBTQ+ space?

EZ: I don’t feel like I’m in a place to give advice to other writers; I’m very much still figuring it all out myself. It is true that queer authors may be facing additional challenges like book bans. But if I were to give them advice, I don’t think it would be substantially different from what I would tell our straight peers. One thing that has helped me personally is making sure that I move my body, ideally with other people. Writing is often such a cerebral, solitary pursuit, and I’ve found great comfort in being physically active, with others, in the world.

WDP: Are you working on a new project now? If so, can you share a little about that project with us?

EZ: Because I work across media—including film, theater, and literature—I have to develop different projects simultaneously. What I end up focusing on often depends on practical considerations like budget and schedules, because I also work as a director. Something about the combination of writing and directing just feels right to me. They balance each other, activating different parts of my soul. To me, writing at its best is a space of total freedom, where all practical constraints dissolve; to do it, all I need is myself and something to write on. But it’s also very lonely, and I’m a creature of collaboration. This is why directing, which involves extensive work with others, feels so fun to me. When I spend too much time at my desk alone, I often find myself missing the film set or rehearsal room.