Valerie Twyman: How do you define inspiration, and how does it differ from talent and technique in the creative process?

Carey Wallace: When kids are little, we tend to identify them as artists because they’ve got more talent than other kids—it’s just easier for them to sing in tune or capture a likeness. Then we train them in technique: the skill that’s earned by spending hours running scales or sketching.

But anyone who has spent much time in the art world knows that talent and technique, even in great measure, don’t always add up to great art. In fact, when we talk about “the most talented person I ever met,” it’s often to lament how little they actually did with their talent.

To create art, a third element is needed: inspiration. It’s what tells the writer what to write and the singer how to sing. It fuses talent and technique and turns them into art. And even without much talent or technique, when people are brave enough to follow the prompts of inspiration, they can make extraordinary things.

VT: Can you share a personal experience where inspiration played a crucial role in your creative work?

CW: I’m a writer who comes from a family of musicians, so when I decided I wanted to write, they said, “Of course you will practice.” That meant I developed a strong creative habit from a young age: when I started college, I also started writing for two hours a day. That habit is how I learned how to write—and it also helped me to produce a lot of work.

But I also remember a moment in college when I had been dutifully doing my writing hours, and was still stuck on a problem in a story. I’d put the time in, turned the story inside out and upside down and shook it out, but I couldn’t find the solution. Then my writing time ended and I got up and threw myself in a chair to stare out the window—and moments later, the solution emerged, fully-formed. I wasn’t grateful. I was furious.

The way the answer arrived made it infuriatingly clear that it was somehow far beyond my command. But it was one of the first clues in my life to the mechanics of inspiration. It taught me how much I needed it to do my work, but also how independent it was of me. And it let me know that I’d need to find different tools than the ones I’d been using to find it.

VT: What example from history particularly resonated with you regarding how people have experienced inspiration?

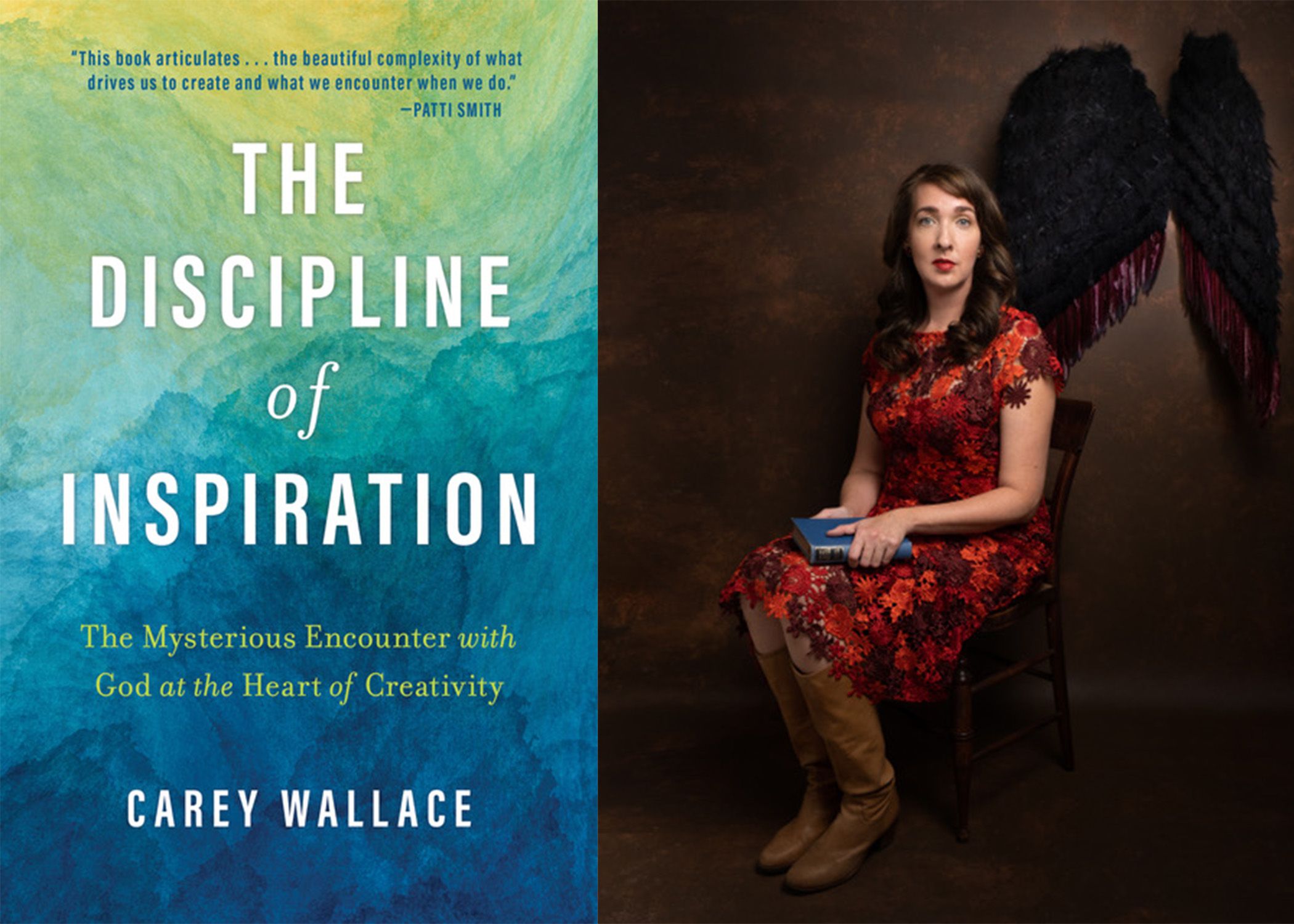

CW: I wrote The Discipline of Inspiration after doing a huge survey of speech by artists throughout history on some of the most important topics in the life of an artist.

The artist’s life: do you have to be unhappy?

The artist’s character: do you have to be a jerk?

What I found was absolute disagreement on basically every topic – from artists so foundational that nobody else had the credibility to argue with them. If Toni Morrison and Tolstoy disagree, which of us is qualified to referee? But in the midst of this cacophony, there was one weird point of agreement, throughout history and across genres: the moment of inspiration.

Again and again, artists described it as something that came from beyond them, that had a personality distinct from their own, that prompted them to do things they hadn’t planned and sometimes didn’t want to do. They described it as having an energy of its own—that if they didn’t respond to it, it would go on to someone else.

And almost universally, regardless of whether they followed a spiritual practice or not, they described it as a spiritual encounter — even if that came in the form of a denial: it feels like meeting God, but that’s not possible.

And many of artists, across traditions and backgrounds, did ascribe inspiration to God, describing it as an encounter with the divine.

VT: How does spirituality intersect with inspiration in your view?

CW: When I read all the testimony of artists on the experience of inspiration, I got very interested in what could become possible if we took the idea that God is present in the creation of art seriously. Some of the most transcendent moments of our lives happen around art. When we create, and when we confront it, we have a sense that we’re touching something beyond this world. What if that sensation isn’t a mirage? What if God is actually present with us when we create, and present with us when we encounter art that others have created? How would that change how we think about God? About art? About ourselves? About the process of creation?

VT: What practical steps can artists take to cultivate and harness inspiration daily?

CW: If we believe the testimony of artists that creating art involves a negotiation with the spirit of inspiration, then the central gesture of creation is surrender: getting out of the way to let that spirit in.

Almost nothing in modern life helps us to surrender. It’s all about clenching, trying harder, more work, more grit, more control. But when I started to wonder how I could get better at surrender in my life as an artist, I realized that I did know a set of tools designed to help us welcome a spirit bigger than ourselves into our lives. I had already been using them in my own spiritual practice, in hopes of growing closer to God: the classical spiritual disciplines, which appear across the major world religions. Disciplines like solitude and silence, fasting, community, manual labor, and prayer.

I’ve come to believe that these practices hold the sum of human wisdom on how to surrender to a spirit beyond ourselves. And I believe that they can be explosively powerful when artists apply them in our lives as creators—because I believe the best things we create flow from a genuine spiritual encounter, and the more we encounter that spirit, the better our work becomes.

VT: Can you share an experience where collaboration with others sparked inspiration and led to a successful project?

CW: Community is one of the fundamental spiritual disciplines, and I also believe it’s a form of art in its own right. It’s not a coincidence that much of the great art in the world has come out of communities, from the friendship between Harper Lee and Truman Capote in their tiny Alabama hometown, to carefully-curated creative powerhouses like Motown.

So alongside my own work as a writer, I’ve spent a lot of time creating communities. I think it’s crucial for artists to recognize that we can build community wherever we are, with whatever we have. We don’t need to have dedicated space or funding. We can share what we’ve got, and invite others to share what they have—and that can be transformative, for all of us.

One way I’ve done this: for years I made soup every Wednesday night, in both Ypsilanti, Michigan and New York City. I invited both old friends and people I’d just met. Soup is pretty cheap to make. People brought their own offerings to add to the dinner. And even though I only had about a dozen seats, upwards of twenty could find room, by standing in the kitchen or squeezing onto the couch.

Over the course of seven years, Soup developed into a deep community, creating friendships that persist today, a decade later. And many artists who joined us, who were unknown at the time, now have a national profile—perhaps in part because of the support and inspiration we gave each other in our creative lives.

Soup is something almost anyone can do, in any space you’ve got. But I hope this story won’t inspire perfect copies of this particular format. I hope it will inspire you to build community in unique ways, anywhere you are, with whatever resources you’ve got—no matter how big or small.

VT: Have you found inspiration from other art forms or disciplines? How do these influences shape your work?

CW: When we’ve got talent or develop technique in an art form, it’s easier for us to cheat when we get stuck: to come up with an interesting distraction to fill an empty space, rather than doing the hard work to wait for the voice of real inspiration.

But art forms where we’re not as comfortable give us a chance to become beginners again. Because we don’t feel like we know exactly what we’re doing, we can’t rush in to paper over holes with our talent or technique. And I think that makes alternative art forms a wonderful place to practice seeking inspiration.

My brother, who’s a highly-trained musician, never wonders what to do when he picks up a guitar or violin. His fingers are full of songs he’s learned, and new chords to try when he hits a wall. But in an art workshop, he was challenged to work in a form he’s not familiar in, and not do anything until he felt the prompt of inspiration. He wound up making beautiful ink drawings on scrap paper with the coffee he’d brought with him.

Much more important, he had a clear encounter with inspiration, outside the comfortable boundaries of his own talent and technique. And he learned a lesson in how to seek and recognize the voice of inspiration back in the contexts where he usually creates.

VT: How has technology changed how you find and use inspiration in your creative process?

CW: I don’t believe technology can help us find true inspiration, because I believe true inspiration is a spiritual exchange, and that the only instrument that can receive it is a human being. Technology may be part of our technique, even a powerful one. But inspiration cannot be generated by machines.

This is very important for artists to recognize, because commercial pressures will always be trying to convince us to act more like machines: to make the same thing over and over, to make things like other things that sold well in the past. Machines may think faster than us. They don’t need to eat or get sleepy. They can recombine things humans have made into all kinds of permutations. Some of their permutations are interesting or beautiful.

But machines can’t make art, because art is the evidence of a spiritual encounter, which a machine cannot have. In fact, as machines seem to overtake us in other ways, they may actually reveal what’s most unique to being human. It’s in our spiritual encounters that we’re at our best and our most human, and we create our best work.

VT: How do you see the artist's role in society, and how does inspiration influence this role?

CW: We live in a world in which almost all forms of speech are now bankrupt. We don’t believe our journalists, our politicians, our religious leaders, our advertisers, or each other on social media. And our ability to communicate is collapsing at a moment when we desperately need to connect, in order to meet the challenges that face us all.

Art may be the last language in which we can communicate with sincerity about the things that matter most, the only site where we can come together and begin to build again. But in order to do that, what we create can’t be propaganda, even for the best possible cause. It has to offer the surprise and complexity, the shifts in perspective, the sting and the balm of true art.

Which means that what we make has to transcend our own narrow vision and limited talents. It needs to come from something beyond us, and welcome something better than ourselves in. It needs to be inspired.