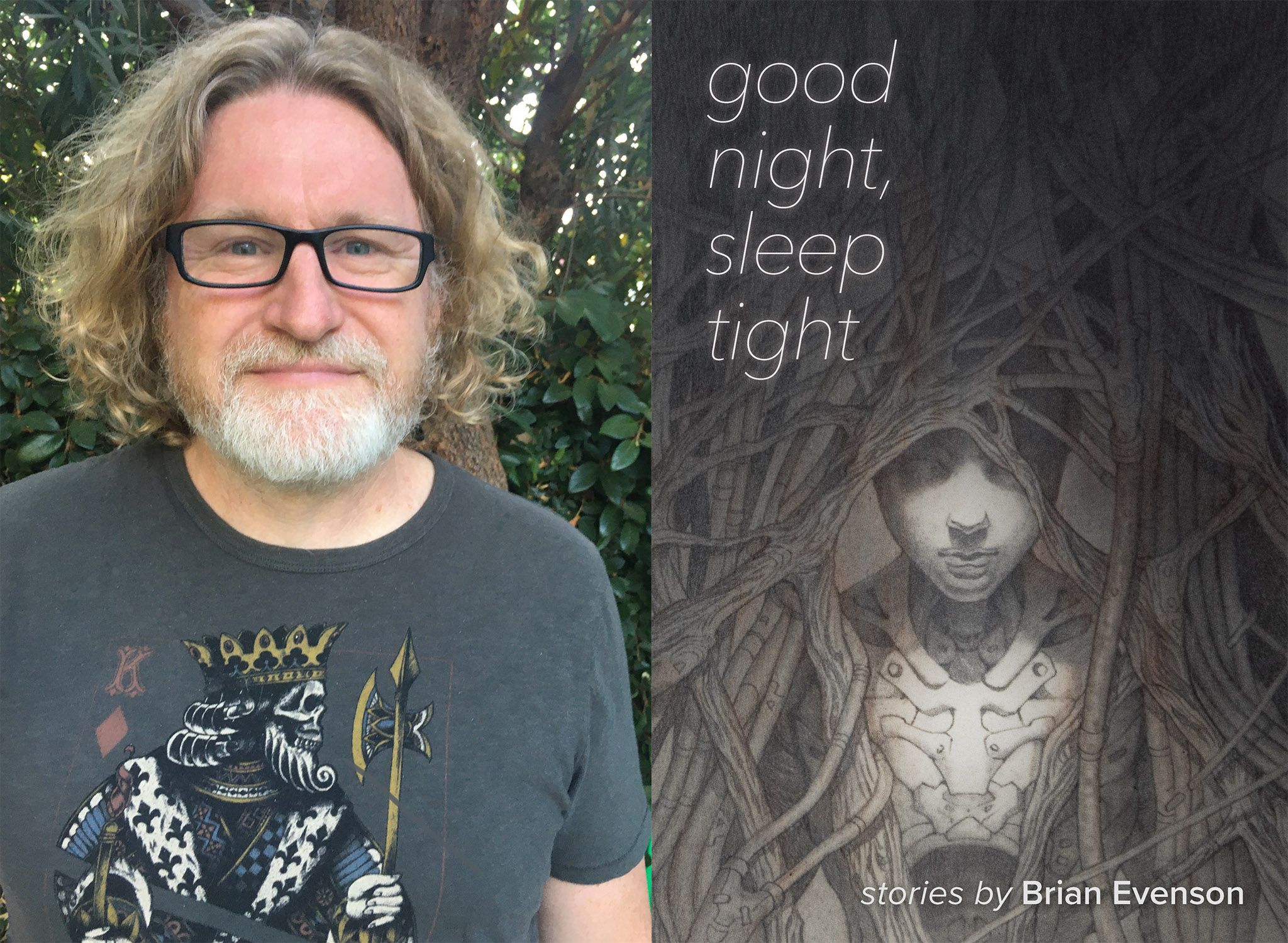

Brian Evenson is the author of almost two dozen books and has received three O. Henry Prizes for his short stories. His book Song for the Unraveling of the World (Coffee House Press, 2019) won a World Fantasy Award and a Shirley Jackson Award and was a finalist for both the Los Angeles Times Ray Bradbury Prize for Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Speculative Fiction and the Balcones Fiction Prize. He lives in Los Angeles and teaches at CalArts. Evenson’s new book, Good Night, Sleep Tight (Coffee House Press, 2024), is a collection of new stories tracing the limits and consequences of artificial intelligence and “post-human” relationships. Populated by twins stepping into worlds of absence, bears who lick their cubs into creation, and artificial humans haunted by their less than human nature, each page sketches a world where our all-too-real feelings of isolation and ecological dread take on an other worldly tinge.

We completed this interview over email with exchanges days before and after the book’s release. We discussed his new stories and some of the craft elements related to their writing.

Brian Evenson on Good Night, Sleep Tight: An Interview about Creating the Reader’s Experience

Brian Evenson on Good Night, Sleep Tight: An Interview about Creating the Reader’s Experience

Todd Poremba: Good Night, Sleep Tight has many stories of children and parents, particularly mothers. Did you have parents and children in mind as significant subjects from the beginning? Or were you surprised by it at some point in the process? When you put the collection together, did you do anything to increase or decrease this emphasis?

Brian Evenson: Usually I write a half to two-thirds of a collection's worth of stories before I start to think of it as a collection. There comes a point in the process when I start to feel the connections between the stories I have, connections which have often been subconscious before, and then I start writing more deliberately, thinking about where gaps are and about what else remains to be explored in the territory. At the same time, I also sometimes discard stories that I initially thought might be part of the collection, saving them for a later collection, and I go back to earlier stories that I haven't collected yet and think about whether they belong here. I think I knew pretty early on that I was writing a fair number of stories about artificial humans, but the way in which those stories took up the ideas of motherhood and what it means to be a child was something I didn't think about much until two-thirds of the stories were written. Seeing that opened up a lot for me in terms of thinking about what kinds of stories I could include and in terms of thinking about what kinds of patterns I was creating.

TP: You’ve said you have one foot in genre and the other in literature and that you have “an interest in what genres and modes can be made to do that they haven’t done already.” Would you say a little about such innovation in this collection on both the genre side and the literature side?

BE: At the beginning of the 20th century, writers weren't for the most part publishing books of stories that were restricted to specific genres. Rather than, say, a book of horror stories you'd have something that was much closer to a miscellany: it might contain a ghost story or two, a realistic story, a detective story, etc. I've tried increasingly to do that with my collections--to make them something in which genre and literary stories can sit side by side and talk to one another. There are common threads and even, mostly, a common mood. But there are also a lot of different modes, and it requires readers to shift or change gears as they read. That's a different experience than reading a book of strictly literary stories or strictly horror or sf stories, and I think the juxtaposition ends up emphasizing the connections that exist across genre.

TP: A lot of readers recognize a Brian Evenson story even with the different modes and shifts, possibly because you are so amazingly skilled at creating mood. How did the themes of artificial humans and motherhood bring you to the different moods in this collection?

BE: I didn’t consciously start out with those as themes. I did, I guess, know I was interested I writing about artificial humans but it wasn’t a conscious thematic: I never thought “This is what I’m going to explore by writing about artificial humans.” It was more like: “What’s interesting about artificial humans and what will happen if I start writing about them?” I think the first of the stories in that mode I wrote was “Mother,” so that connection between artificial humans and motherhood was already there. Then the stories I wrote after that began to look at new facets of those ideas, extend it out in different directions, see where else it would lead me. The connections are complex and intuitive.

TP: You’ve mentioned how some of your stories are responses to other writer’s work. Your story “Rider” in this collection seems to be in conversation with Robert Aickman’s story “The Hospice.” Aickman’s story has some funny moments in it. Your story has similar humor. Would you comment on this particular conversation with Aickman’s story? Generally, how do you use humor alongside horror in a story?

BE: I love Aickman's "The Hospice." I can see how you might feel a connection there, and Aickman has definitely been a huge influence on me ever since 2006 or so when I discovered his work. I think there's an Aickman feel to "Rider" but it's more connected to one particular Ramsey Campbell story, "Reading the Signs," which was the story that inspired it. But of course, Campbell was influenced by Aickman as well, so... I tend to like stories that have a humorous element as well as a horror element, in that the humor can both provide a little relief but also make people put their guard down a little, which lets the horror worm its way in more effectively. For me the humor is often dark and morbid and absurd. In that sense I feel very strongly connected to Kafka, who I think can be very bleakly funny-- though a lot of people don't seem to notice that about his work.

TP: With 30 years of publishing work, you seem to also be in conversation with the younger Brian Evenson. I’m thinking, for instance, of “Windeye” from the collection of that name and “The Sequence,” the first story in Good Night, Sleep Tight. In writing some of these new stories, were you deliberately conversing with your earlier work? What are some ways your earlier writing gives you insight to your current writing and vice versa?

BE: I'm always communicating with work I've already written, partly because I'm sometimes trying to figure out how to create an effect that I've created before but to do so in a new context, partly because often a story will approach one facet of an idea and there's still more to explore if you turn the idea just a little. Yes, "Windeye" and "The Sequence" are definitely in conversation.

I love "Windeye" which was, a breakthrough story for me and which, I feel, does a tremendous amount with very little. "The Sequence" extends the ideas of "Windeye," though, by giving a view of the alternate world. I just reread my first collection, Altmann's Tongue, because it's coming out in a thirtieth anniversary edition this year. It was a very strange experience in that there were some stories that I remembered perfectly and other stories that I didn't remember much at all. I probably remembered the ones I did because they were stories that served as steppingstones to where I am now and are clearly part of a genetic trunk that led to the Brian Evenson I am today. The others seem more like branching off the trunk, directions I could have pursued aesthetically but which I ultimately didn't. It was actually really fun to read the stories I didn't remember as well because it was like reading an alternate reality version of me.

But having said that, I don't tend to go back and reread my earlier stories and novels, unless I'm reading them aloud in front of an audience or unless a book is being reissued and I have to...

TP: You’ve commented about how your writing has changed at the level of the sentence, for example, reusing the syntax of church rituals or adopting syntax from another language. Would you comment on how your sentences have developed over your career? Are there any sentence structures that were a change for you in this collection?

BE: This is a really tough question and I'm not sure I can fully answer it. I guess what I'd say is that there are things that have happened with my style over the years, but they happen so gradually I don't think I can identify a change from book to book. I do think my language has always been very precise but my approach to other aspects of fiction were more akin to Minimalism early on, that my writing has become more expansive and a little more open. I think it's also become emotionally more open as well, that I'm willing to talk about things that early on I would have passed over in silence. A story like "Imagine a Forest," for instance, is not afraid of moving into an intense emotional space. The stories in my first collection, by contrast, occasionally skirt such a space but usually touched it just by implication if at all (like in the first story of that book "The Father, Unblinking"). But in terms of sentences, I feel like I'm always experimenting, always trying things, trying to take risks...

TP: Some of the most direct emotions in the collection come from non-human, post-human narrators. Some of these narrators seem like better companions and better stewards of the world. These stories, to me, revisit The Warren and Immobility but take the themes in a new and more radical direction. Would you comment on this new version of the future?

BE: I do think that posthumans are probably going to be better at taking care of the world than we are, perhaps partly because of the way their neural networks are created but also because, honestly, I don’t see how they could be much worse. And they’ll have the example of all that we destroyed. In terms of companionship, too, it’s not that humans can’t be good companions but just that part of being human is that you get tired and angry, you get jealous, you become selfish—along with all the good parts as well. I see at least some of the posthuman stories as being about artificial beings learning to be like humans—but also making choices sometimes to not be like humans in certain ways…. And yes, there are definitely some connections to The Warren and Immobility, though not as direct of connections as those two books have to one another.

TP: You once commented that Muriel Spark, as a fiction writer, is someone “who looks safe until you look at her closely.” I feel that applies to some of the stories in this collection. Would you comment on how you and Spark make a story look safe and what experiences you suspect readers will have if/when they look closely?

BE: I think the reading experience is a combination of familiarity and surprise. If it’s too familiar, it may not be that interesting to read. If it’s nothing but surprise it can be exhausting and you can lose interest. So much of what I do, despite how dark some of my work can be, is about creating a subtle empathy in the reader, drawing them in, getting them invested in what’s happening to the degree where they start to almost be participants in the story: wondering where it’s going. And the trick is to try to do that subtly enough that they don’t feel that they’re being manipulated. If you do that properly, they will trust you and will also open themselves up so that they have a more intense experience with the book. To do that, I think, you have to be willing to share that experience. It’s not about scaring the reader or tricking the reader: it’s about accompanying them.

TP: Once readers have finished your new book, Good Night, Sleep Tight, how long will they have to wait for Phantom Limb? And can you say a little bit about that book?

BE: Good question… I think it won’t be out until 2026, but we don’t have an exact release date yet. It will, however, be coming out in France before that, probably Spring of 2025, so if you read French, you can read the book a year before anybody else. Last Days also came out in France before it came out in America, so it feels appropriate that the sequel would as well.

I don’t know how much about it I can say without giving too much away. I’ll say, I guess, that Kline is in the book, and that he’s been arrested when the book opens. There’s a different religion involved, one that’s more mystical and ecstatic, and Kline does risk becoming a believer. I’m not even sure I should say that much.

TP: In your interviews, you’ve been very generous with supplying additional reading for those of us who love your work. So, after everyone reads this one, would you share what five books, give or take, that are just out or about to come out that you are looking forward to reading or have just read yourself and enjoyed?

BE: I recently read the galleys of Michael Wehunt’s,The October Film Haunt," which I liked a lot. It’s his first novel and is based on a story from one of his two collections—both of which are terrific. It’ll be out in 2025. I also just finished Laird Barron’s Not a Speck of Light, which was an excellent collection. Almost nobody else writes such consistently good horror stories. Julia Elliott’s Hellions, which will be out in 2025, is a great fantastical collection, literary and southern gothic in feel. I’m looking forward to reading Nora Lange’s, "Us Fools," about the complex relationship between two sisters during the midwestern farm crisis of the 1980s. And I absolutely loved—maybe my favorite book I’ve read this year so far—Josh Malerman’s "Incidents Around the House," which is a scary and heartbreaking possession novel.

Todd Poremba

Todd Poremba works in technology in Seattle, Washington, and is an MFA candidate in fiction writing at the Vermont College of Fine Arts.