Montserrat Andrée Carty: In your author’s note you quote Susumu Tonegawa: “recalling a memory is not like playing a tape recorder. It’s a creative process.” Can you talk a bit about memory and memoir? About writing your own metaphoric truth, as you say.

Sue William Silverman: Right: Creative nonfiction works aren’t academic treatises or legal documents meant to stand up in a court of law. Rather, writing memoir or personal essay is a search for emotional truth—not a search for a fact. How do I best recall events from the past? I first try to immerse myself in the senses—the sensory memories around a past event. What imagistic details convey the experience? Once I retrieve those, I convey them in such a way that they shed light on the narrator’s interiority. This is how we achieve metaphor.

Let me give you an example. One essay in Selected Misdemeanors, “Psych Ward, Drought,” explores a time when my emotional misdemeanors were catching up with me. So, I could have straightforwardly, and rather factually, written the basics of what I remembered off the top of my head: “One summer when I lived in Georgia, my husband was out of town, and the air was hot and stifling. It hadn’t rained in weeks. And, honestly, what with the heat—on top of my husband’s abandonment—I was lost and depressed and thought I was having a nervous breakdown.”

But those “facts” are rather boring and don’t convey metaphoric emotional truth. Therefore, here is what I actually wrote in the essay: “My fantasies ranged from cloudy skies to soft drops of water to a deluge of biblical proportions. In the dryness—maybe I fantasized it, maybe I didn’t—I heard random things cracking. Like coffee cups in the pantry. Egg shells in the refrigerator. Needles of loblollies. Legs of daddy longlegs. Strands of my hair. The top of my skull. This was the final motivation I needed to drive to the psych ward at the local hospital on September 1. I’d had it.”

By describing those sensory images outside of myself (coffee cups, egg shells, strands of hair), I metaphorically depict that interior feeling of loss and depression: that I was cracking. Could I have stated this feeling at that actual time in the past? No. Only the author “me” in the present, through writing and the use of metaphoric memory, is able to artistically convey that moment in the past.

In this way, I am better able to bring the reader inside the experience. A reader can’t relate to abstract words such as “loss” or “depression.” Those words are generic. But by artistically showing the feeling metaphorically via slanted tangible imagery, the reader can feel or imagine what the narrator is feeling.

MAC: Several of these essays involve the narrator eavesdropping. Do you think this is essential to being a writer? I was thinking recently about how funny it is that as writers, we are both so attuned to our surroundings (noticing all the tiny details, fleeting moments and conversations) and yet, also live so much in our own heads, right?

SWS: That’s interesting to think about the relationship between writing and eavesdropping. In one essay, “Emerald Isle,” I, as a young narrator, stand on the verandah of my home on St. Thomas spying (eavesdropping?) on one of my parents’ fancy parties. The guests don’t interest me, however. Rather, the long-stemmed glasses of crème de menthe, do. As a child, I merely loved the color; only later, when writing the essay, the narrator envisions “small seas rippling green tides of joy.”

In short, the crème de menthe is only a liqueur until I write it, scrutinize it, slant the sensory imagery in such a way to determine its deeper or more universal meaning. In this instance, the revelation is how beauty and joy are discovered in ephemeral moments. But if I hadn’t originally spied on this party, I would never have captured this moment. In short, the writer, even before she’s a writer, learns so much by silently observing.

Additionally, in a more global sense, I constantly “eavesdrop” on the world around me, by observation. Maybe I’m searching for clues about life? Or making sense of my milieu, my environment. In this way, each of the 71 essays in Selected Misdemeanors is a result of eavesdropping.

MAC: Let’s talk about form! Most of these essays are what we might call “flash” or “brief” nonfiction. This has become the kind of CNF I most love to read and write. I am curious to know what draws you most to this form?

SWS: Ha! Initially, desperation! I’d already written two long-form memoirs. I’d also written two memoir-in-essays collections. What else could I possibly write about myself? I had to figure out something!

Then it occurred to me how obvious it is to be aware of the big moments in our lives, events that immediately present themselves as material to write about: damaged childhoods, addiction, divorce, marriage, loss of a loved one, raising children, losing one’s home or country, war, etc. But, when you think about it, these big moments don’t usually take up the majority of our actual time over a life. So what about all the short or brief moments between these big ones? That’s a lot of time, right?

Therefore, I became fixated on all these so-called “smaller” increments of time and what kind of meaning they held. Well, I would only find out by writing about them.

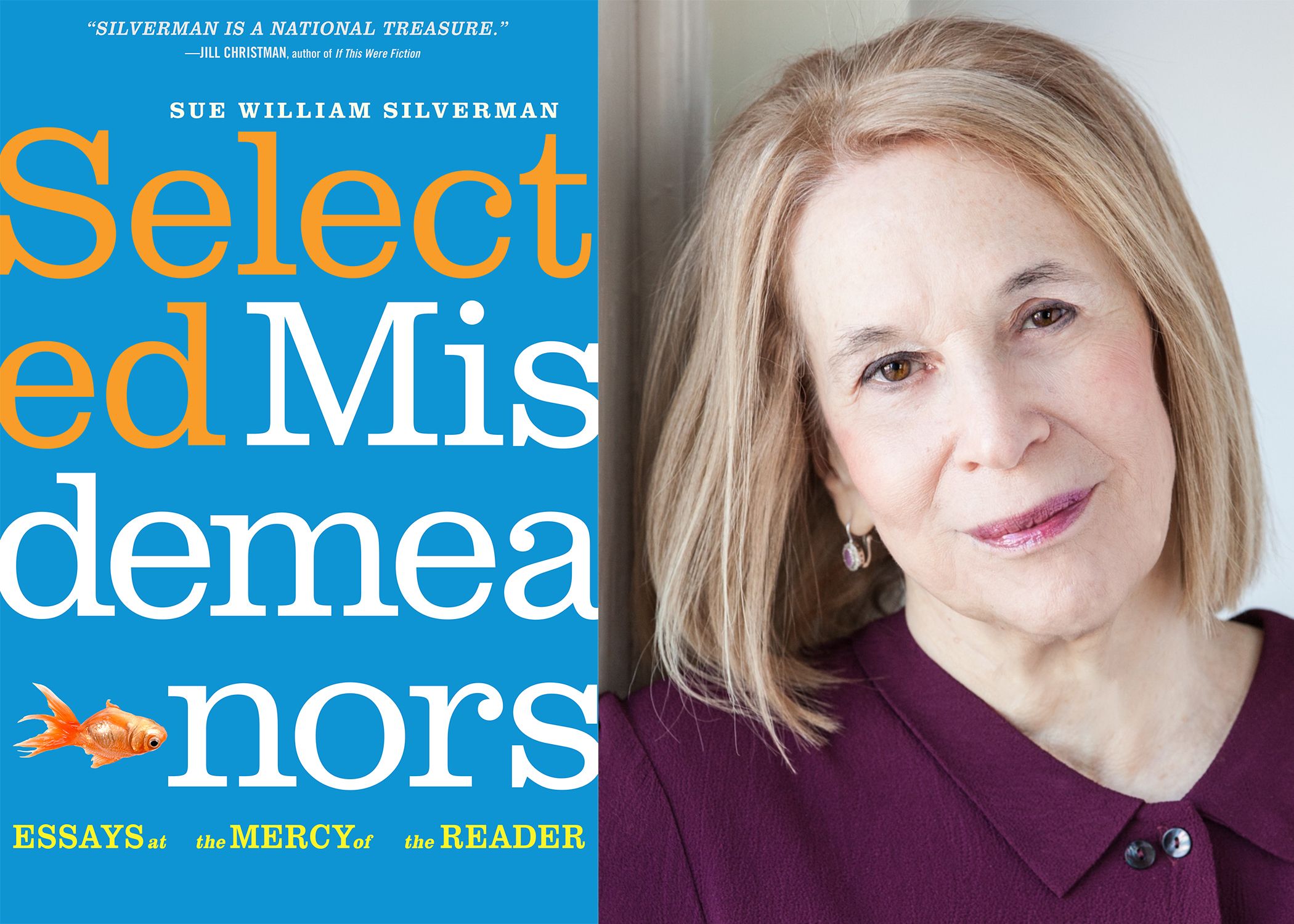

For example, on the cover of Selected Misdemeanors is an image of a goldfish, belly up. This goldfish is in the essay “Love Deferment,” and, on the face of it, how could I possibly find anything of note to say about a dead goldfish?

Well, here is how the essay evolved: After my unloving boyfriend leaves for boot camp, I buy a goldfish for company. Also for company, I betray my boyfriend by having an affair with his roommate. One of my misdemeanors is that relationship. Then, when the roommate breaks up with me, I’m so distraught I forget to feed the goldfish. Who dies. Another misdemeanor. But this goldfish evolves into a metaphor because he encapsulates more than just my misdemeanor of forgetting to feed him. The fish, within the context of this essay, is a metaphor for betrayal and the loss of love.

Those are the instances that I write about in Selected Misdemeanors. Things that might not, on the surface, immediately seem like a topic for an essay—say, like the aforementioned crème de menthe. My advice? Dig deep! You might well find the significance in fleeting spurts of beauty, miniature forms of betrayal, microscopic snippets of loss.

MAC: I love the way you bring photographs in the book! Can you talk about that process a bit?

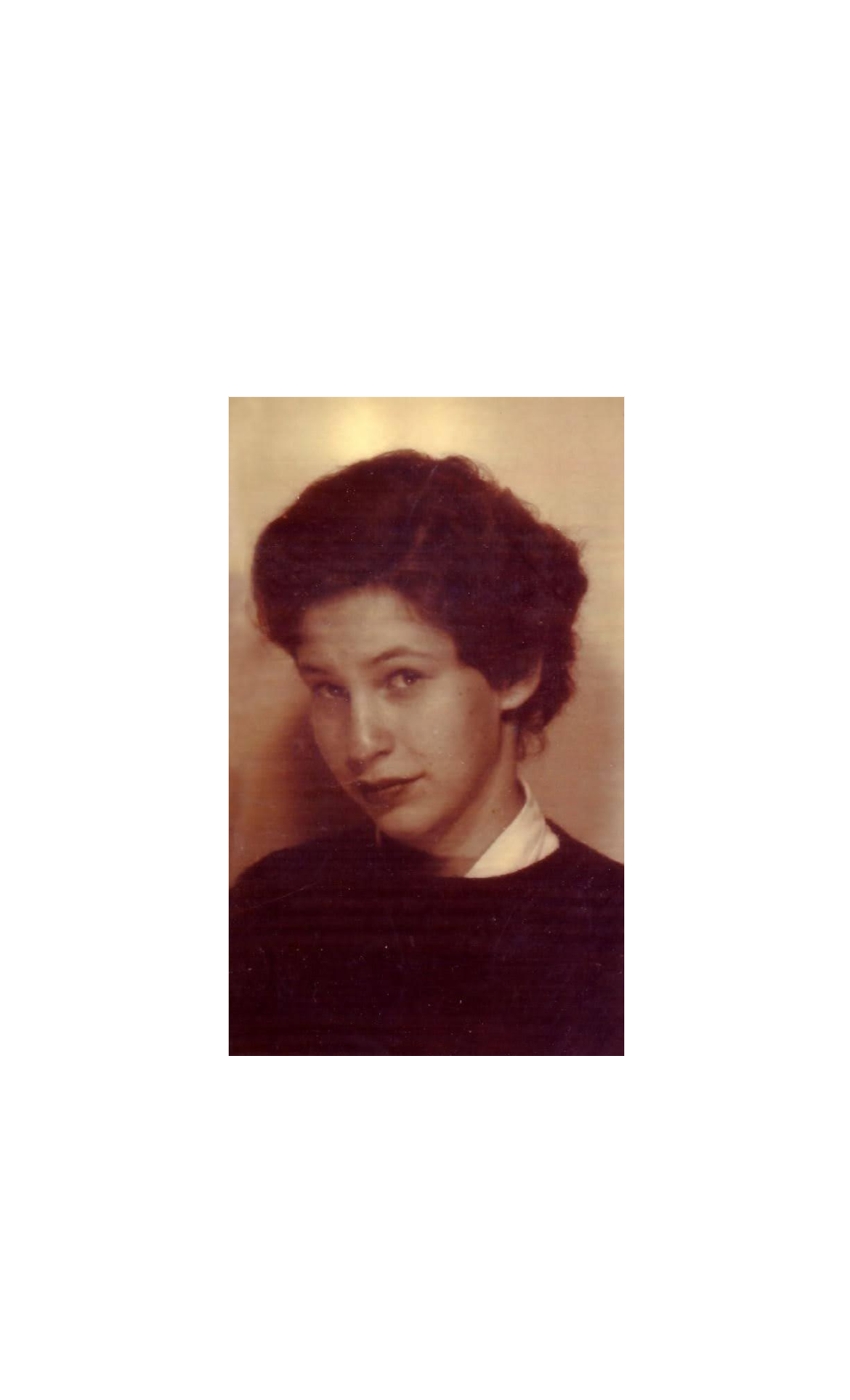

SWC: I didn’t want photos merely to showcase or speak to a specific essay. Rather, the photos are actually essays unto themselves.

Therefore, each has a (long) title meant to establish the essence of the photo. These titles all begin with a created persona, “Miss Demeanor.” The titles are followed by the photos, which are then followed by short, three-line essays about the photo. Here’s an example of one of the photo essays:

“Miss Demeanor Considers the Time She Hid in a Curtained Photo Booth at a Carnival and Produced a Snapshot that Captured for the First Time the Addict’s False Eyes, the Innocently Deceitful Gaze of her True, Pre-clinical Self”